Editor’s note: Amigos805 welcomes guest columns, letters to the editor and other submissions from our readers. All opinions expressed in submitted material are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the viewpoint of Amigos805.

By Armando Vazquez / Guest contributor

I was moved to revise this article that I wrote previously. I recently saw the Netflix documentary Carlos Almaraz: Playing with the Fire. The documentary on the life of Almaraz was co-directed by Elsa Florez Almaraz, an artist and wife of the late Almaraz, and Richard Montoya, one of the founding member of the Chicano theatre group known as Culture Clash. The documentary Carlos Almaraz: Playing with Fire is a unique, revealing, at times painful look into one of the greatest American artist of the 20th-21st century. The Playing with Fire documentary reveals in honest detail the many battles that Carlos fought through to eventually find his true artistic style and genius. It was not easy for this young Chicano kids who was growing up ambivalent and lost in California, where he did not seem to fit in anywhere.

Carlos was always a gifted and talented artistic, he had early dreams of working for the Walt Disney studio, it did not pan out. Later and still in his development and exploratory period as an artist desperately looking for divine inspiration he travelled to New York City. It was in this period that Almaraz would rub shoulders and work with the giants of the New York American Modern Art scene, artist like Andy Warhol, Jasper John, Robert Rauschenberg, Phillip Fagan and Gerard Malanga, and others; much as he tried and struggled Carlos did not fit the New York art scene. He left the New York art scene of the 1960’s as a despondent and frustrated artist.

In self-imposed exile, from friends and family, Carlos decided to travel throughout Europe. In Europe Carlos found himself, lost again, as an artist, and with a nasty alcohol problem that was exacerbated by an acute sexual identity crisis. The heavy drinking almost killed him. He sought help, eventually sober up enough to return to America, but not before Almaraz witnessed throughout Europe the intimate connection between art, revolution, the competing ism’s and social upheaval that was rocking the world in the 1960’s. Carlos decided to return to California, and it was upon his return to California Carlos plunged himself completely in the revolutionary fire of the Chicano Movimiento. Carlos had finally found his calling and lending his prodigious art talent to United Farm Workers (UFW) movement that at the time was being led by Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta. He, also, got involved with Luis Valdez and his Teatro Campesino Troup, and finally began to work with other Chicana/o artists of East Los Angeles in a united effort to storm the doors of the Los Angeles art and museum world that up to that time was closed, with a “Chicana/o artist not welcome” signed at the front entrance. As a young Chicano activist artist, in the period around 1965-1970, I followed with love, admiration and anticipation the development of the Chicana/o revolutionary art scene in East Los and throughout Califas. It was at this critical juncture in my artist/activist development that I would jump in began playing with the fires of art, revolution, and liberation.

My high school, San Fernando, located at the time in the very segregated, racist and conservative San Fernando Valley, California, suffered through student riots in both 1968 and 1969. I remember vividly the graffiti that documented our angst, anger and audacity of the time, “Education not Prisons”, “F—- the Pigs”, “Chale con Vietnam”, “Support the UFW-Boycott Grapes”, “Venceremos” and my favorite “ Todo Poder al Pueblo-Power to the People”. Spray can in hand I was actively involved in the liberation of the school walls and in spreading the revolutionary messages of the Chicano Movimiento. Along with my homies we articulated a poetically crude but honest assessment of the violent, hostile, alien, and foreboding world that seemed to be closing in on us.

Due directly to the social upheaval and the student maelstrom that sucked most of us in the Americas and the world into its intoxicating vortex I became a social justice activist, I became a Chicano artist. It was in high school that I turned my passion and attention away from athletics to social justice activism, using my art as my newly found weapon. Throughout the Southwest many Chicano artists joined in the Movimiento and used their artistic skill and talents to support The Chicano Movimiento in our struggle for equality and social justice.

From this chaotic and exhilarating student driven and lead revolutionary struggle beginning the Chicano Art Movement. Almost from the inception the Chicano Art Movement soared and roared, helping to articulated, documented the many trampled, blunted and deferred aspiration, dreams and struggles of the Chicanos in the United States and in particular in our barrios throughout the southwest. Many of us turned to our Mexican art maestros, the original revolutionary artists from the turn of the 20th century, for guidance and inspiration.

Here, dear reader, is where social justice and art history, and this story, takes a wonderful and insightful turn; and an affirmation that I have been asserting now for 50 years. Namely, that the Chicano Art Movimiento is the incontrovertible revolutionary progeny of the Mexican Revolutionary Artist, and as such the continuation of the most influential art movement of the 20th-21st century.

The Mexican Revolution began in 1910, and is recognized as the first major political uprising and revolution of the 20thcentury. At the vanguard of the Mexican Revolution where warrior peasants like Villa, Zapata y Las Adelitas, intellectuals like Jose Vasconcelos and artists like Jose Posada and Francisco Goitia all working to over throw the brutal dictatorship of Porfirio Diaz. It is during this protracted and bloody civil war, and the turbulent years of reconciliation that follow that the Mexican artists would take the center stage in documenting the painful and sputtering transformation of Mexico from tyranny to a fledgling democracy, and the social justice aspiration of Mexico and the 20th century world.

In a recent fascinating article written by Natasha Gural, a multiple-award-winning journalist, which center around the ground-breaking, revolutionary and historic exhibition entitled Vida Americana: Mexican Muralist Remake American Art, which opened at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York on February 17, 2020, Grual quotes Barbara Haskell, the world renowned art historian and curator of the Vida Americana exhibition that, “the Mexican artists had the most profound and pervasive influence on American (the Americas) art of the 20th century”

World renowned art historian Barbara Haskell and Armando Vazquez, Chicano artist, writer, and curator from Chiques, Califas concur and thus dismiss outright the Eurocentric, racist, and prevailing myth that the French, or the Germans or the Spanish; or in fact any and all art that emanating in Europe had the greatest impact on artists of the Americas and the world. Haskell research of over 10 years for the preparation of the Vida Americana exhibit lead her to conclude that 20th century Mexican art is, “an epic, socially moving document” that influenced the 20th century art world, “South to North, rather than East to West”

The Vida Americana exhibitions highlighted over 200 works and more that 60 artist both Mexican and international renowned artists that were deeply influenced by the Mexican Maestro Artistas that include: Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, David Alfaro Siqueiros, Miguel Covarrubias, María Izquierdo, Frida Kahlo, Mardonio Magaña, Alfredo Ramos Martínez and Rufino Tamayo, Thomas Hart Benton, Elizabeth Catlett, Aaron Douglas, Marion Greenwood, William Gropper, Philip Guston, Eitar? Ishigaki, Jacob Lawrence, Harold Lehman, Fletcher Martin, Isamu Noguchi, Jackson Pollock, Ben Shahn, Thelma Johnson Streat, Charles White, and Hale Woodruff, among other giants of the 20th century art world.

David Alfaro Siqueiros, Proletarian Mother, 1929 Diego Rivera, Man, Controller of the Universe, 1934 Siquieros, Echos, circa 1934

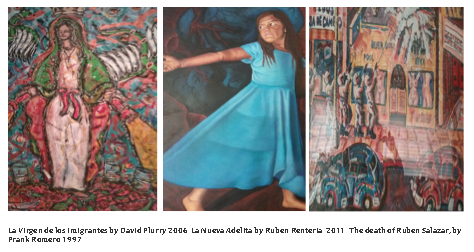

The Mexican Revolution and Chicano Movimiento were forged in the blood, terror and death of war, art became one of the indispensable weapons of communication for the struggling masses. For over half a century Chicano artists, like the Mexicans before them, have been documenting as Barbara Haskell put it “an epic, socially moving document” Chicano art maestras/os like Judithe Hernandez, Beto De La Rocha, Margaret Garcia, David Flurry, Pattsi Valdez, Frank Romero, Judith Baca, Carlos Almaraz, Linda Vallejo, Frank Martinez, Jaqueline Biaggi, Lalo Garcia, Diane Gamboa, Margarita Cuaron, Yreina D. Cervantez, Magu, Leo Limon, Maya Gonzalez, Carmen Loma Garza, John Valadez, Joe Bravo, Guillermo Bejerano, Sergio Hernandez, Yolanda Lopez, Linda Vallejo have continued with the epic art documentation of the Mexican/Chicano Art Movimiento here in the United States.

La Virgen de los Imigrantes by David Flurry 2006 La Nueva Adelita by Ruben Renteria 2011 The death of Ruben Salazar, by Frank Romero 1997

If you have been an astute and passionate buyer/collector of Chicano art dear reader then you are in the enviable position of owning some of the most influential and important contemporary art in the world today.

That is why it is such a shame and disgrace that cities like Oxnard (80% Chicano/Mexicano) with its artistically/culturally bankrupt politicians and functionaries reject and dismiss overtures by prominent Chicano artists and community leaders/activists to begin the creation of a Chicana/o Latino museum in the community. Nothing creates community awareness, pride and progressive civic direction and economic development faster than a culturally sensitive and congruent art and cultural scene in a local community struggling for identity as is the downtown sector of Oxnard. Currently, the Carnegie Museum, once one of Oxnard cultural jewels, it is locked up and abandoned. Why not turn the Carnegie Museum to the Acuna Art Collective?

The Acuna Art Collective and our many community partners have tried for over three decades to generate and garner the support from city politicos and officials of Oxnard to convert one of the many abandoned building in the downtown area into a Chicano/Latino Art Museum, it has fallen on hostile and culturally tone deaf ears. I will not stop in my effort to create in Oxnard and other communities of Southern California multiple Chicano/Latino Art Galleries and Museum. These art and cultural institutions are desperately needed to educate, inform and inspire the next wave of Chicano artists/activists and their supporters to work for equality and social justice for all by continuing to utilizing the arts as one of the most powerful and transformative weapon of the 20th century.

— Armando Vazquez, M.Ed., founding member of CORE and the Acuna Art Gallery and Community Collective.