By Amy Bentley / UCSB

Many miles away from the popular Mexican seaside resort towns of Puerto Vallarta and Cabo San Lucas lie the poor, rural villages of Mexico’s Mixtec people, also known as “the People of the Land of the Rain.”

The Mixtecs originally developed communities isolated by the hilly Oaxacan terrain, with many remote villages accessible only on foot. The arrival of Spanish colonizers in the 1500s brought Catholicism to these communities, and it became a major force — both religious and social — that faces huge challenges in the face of globalization and religious conversion in modern-day Mixtec society.

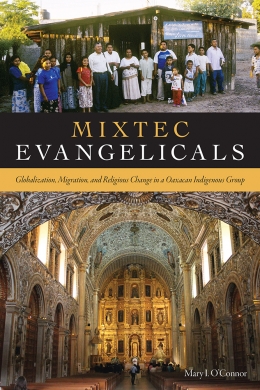

In her new book, “Mixtec Evangelicals: Globalization, Migration, and Religious Change in a Oaxacan Indigenous Group” (University Press of Colorado, 2016), UC Santa Barbara scholar Mary I. O’Connor compares four Mixtec communities, highlighting how economic migration and religious conversion have changed the social and cultural makeup of predominantly folk-Catholic communities. Globalization, she says, is at the heart of this process.

In her new book, “Mixtec Evangelicals: Globalization, Migration, and Religious Change in a Oaxacan Indigenous Group” (University Press of Colorado, 2016), UC Santa Barbara scholar Mary I. O’Connor compares four Mixtec communities, highlighting how economic migration and religious conversion have changed the social and cultural makeup of predominantly folk-Catholic communities. Globalization, she says, is at the heart of this process.

O’Connor, a researcher with UCSB’s Institute for Social, Behavioral and Economic Research, presents case studies and data from 10 years of ethnographic field work in Oaxaca communities in Mexico and the western United States. She describes the effects on the home communities of the Mixtecs who travel to northern Mexico and the U.S. in search of wage labor and return having converted from their rural Catholic roots to Evangelical Protestant religions.

“Globalization is a very important process that is affecting everybody in the world, even people in little villages,” O’Connor said. But the Mixtec people have managed to stay close to their roots.

“That’s very important to them,” she noted. “They still identify with their villages even though they haven’t been there in years. They have maintained this huge network that covers the area from Washington State to the Mixteca region. They’ve invented this whole response to globalization and created transnational communities. Within these is the possibility of religious conflict that they have adjusted to.” O’Connor noted, for example, that converts challenge the old customs of their villages by refusing to participate in traditional village activities such as Catholic ceremonies and social gatherings. Villages cope in different ways, from partially accepting the converts to expelling them entirely.

“It’s basically unknown that there are significant numbers of Mixtecs that are converting and that there are significant numbers of Mixtecs in the U.S. as a result of globalization,” she said. “Globalization is changing the culture and religion of these people who live in these remote villages. They only started to convert when they began migrating.”

O’Connor’s interest in the subject was piqued 15 years ago when she discovered four congregations of Mixtec Pentecostals in Santa Maria and learned that many were converting to non-Catholic churches. She was surprised because Evangelicals reject the Catholic saints as false idols, and do not drink alcohol, which is an important part of all Mixtec Catholic festivities. She writes in the book’s introduction, “It seemed apparent that once Evangelicals returned to their villages, they were on a collision course with the Catholics, as well as with the major traditions that are the basis for Mixtec transnational communities.”

O’Connor studied four Mixtec communities in Oaxaca, including one inhabited entirely by non-Catholics who had been expelled from their village for being non-Catholic. She also studied Mixtecs in other areas of Mexico and the western U.S. to learn how they adapted.

Before visiting the Mixtec villages, O’Connor needed permission from local Mixtec community leaders and various committees of residents. “It took a while in each case to get permission to be in these villages and sit down with people and talk to them,” she said. “I had to go to the meetings of the authorities in each village and talk to them and explain what I was interested in. They were very, very worried that I was a missionary. They didn’t recognize me as somebody who was not going to hurt them. Outsiders have hurt them a lot.”

A UCSB alumna, O’Connor earned Bachelor of Arts degrees in anthropology and Spanish, and a Ph.D. in anthropology from UCSB. Her research was supported by grants from the UCSB Interdisciplinary Humanities Center, UC MEXUS and the UCSB Office of Research. Funding from the Fulbright-Hays Faculty Research Abroad Program enabled her to spend a year in Mexico studying the four communities.