Ena Swansea, area code, 2019. Oil and acrylic on linen, 108 x 82 in. SBMA, Museum purchase with funds provided by Kandy Budgor; Luria/Budgor Family Foundation. © 2019 Ena Swansea. Image courtesy of Ben Brown Fine Arts. Courtesy images.

Exhibition explores art that confounds an analog v. digital divide

On View through August 25, 2024

SANTA BARBARA — The Santa Barbara Museum of Art’s (SBMA) exhibition Made by Hand/Born Digital features 12 artworks and 9 artistswho use brushes, AI, paint, 3D printers, scissors, magazines printed on paper, digital looms, potter’s wheels, Photoshop and Apple Photo. By continuing to craft ceramics, paintings, and textiles by hand and also using the latest digital tools, many of the artists in the exhibition blur a distinction between the handmade and digital. Collectively, these artists remind us that computers are tools—exquisitely complicated but still tools—made by and for humans. They allow artists to work faster, experiment before committing precious time and materials, toss the dice of chance to see what AI might conjure, or easily produce minutely wrought labor-intensive details. Their art demonstrates that silicon-based intelligence and our carbon-based mammalian brains can and do work together as well as suggesting an alternative to inevitable digitization of everything. With a mixture of recent museum acquisitions and loans of artworks by Alex Heilbron, Taha Heydari, Yassi Mazandi, Justin Mortimer, Analia Saban, Ena Swansea, Sarah Rosalena, Joey Watson, and Pae White, this exhibition shows that the traditional mediums—painting, ceramics, and weaving—can incorporate the methods offered by digital technologies to erode a clean distinction between the digital and handmade. Perhaps, the biggest lesson is to ignore hype about the latest transformational gadget or app and, instead, pay attention to what artists are really doing with technology and see how they channel cutting edge tools to deal with the age-old struggle of giving concrete visual form to ideas and pictures inside their minds.

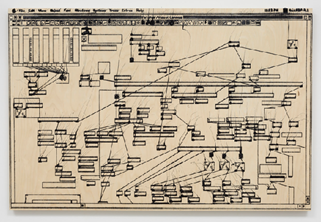

Analia Saban, Pleated Ink (Music Synthesizer: Max/MSP, 1996), 2020. Ink on panel, 30 x 44 ¾ in. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. © Analia Saban

Many of these artists are painters who still work with brush, paint, and stretch canvas, who have no obvious relationship to computer-aided methods. It was discussions with these painters that crystallized the theme of this exhibition. Alex Heilbron’s layered geometric compositions mix machine-cut acrylic stencils with paint. She turned to the computer-made stencils to save time and free up her practice. Taha Heydari’sReterritorialization (2023) shows a ramshackle greenhouse with water pouring from the ceiling and people milling around as if for a picnic. This sci-fi dystopia began as an AI-generated picture that he substantially manipulated by, among other things, adding highly textured areas of paint. Ena Swansea began her process by spending time at her computer going through the tens of thousands of photographs she has taken, saved, and archived. She does not sketch on the computer. Rather, the pictures on the screen coalesce into fuzzy generalized pictures in her head that then guide the painting’s execution in front of the canvas. For the painting Dog (2010), Justin Mortimer cuts and collages from paper magazines, feeds a collage into Photoshop, manipulates and experiments with the program, and only then returns to the canvas.

Like the paintings in the exhibition, Yassi Mazandi’s Nine (2023) has the look and feel of having been made by a person with its nubby and barnacled surface. It began as clay thrown on a potter’s wheel that she then carved and fired. After firing, it was X-ray scanned, which became a digital file. An enlarged version was then printed with an experimental machine that uses pulverized stone bonded with a magnesium compound. Finally, Mazandi brushed on a coating to heighten the resemblance to something submerged in the ocean. Similarly, in Phosphenes (Partial Cataracts 11)(2013), Pae White deployed a computer-controlled laser to burn off thin layers of paper and ink. It is like printing in reverse, removing material rather than adding. While clearly machine-made and completely dictated by the program, there is a feeling of spontaneity or unpredictability in this hazy patterned veil that recalls the controlled chaos of a sputtering inkjet printer running out of ink.

Analia Saban’s Pleated Ink (Music Synthesizer: Max/MSP, 1996) (2020)represents a computer desktop running the synthesizer program Max/MSP. Innovative for its time, the program used what is called a Visual Programming Language, meaning instead of typing lines of commands, the user moved blocks, lines, and graphic symbols to operate the synthesizer. With its wisps of ink pigment that stretch like taffy, the painting gives the normally flat and dimensionless computer monitor texture, heft, and material presence. Saban pulls the experience of the monitor, one that we experience daily, back into the realm of corporealized world and reminds us of what we might be missing while tethered to the screen and scrolling for hours at a time.

Using indigenous and ancient techniques of dyeing and a digital loom, Sarah Rosalena (Wixárika) makes a powerful statement inExit Grid (2023) about mathematics being disconnected from human lived experience and the natural world. Grids, a mathematical construction, can be tools to explain and rationalize but also are tools to oppress and control. With a spectrum of colors and loose weave, she has eroded this grid, as if it were something vegetal, growing beyond its neat squares.

One of the comforts of the handmade is its accessibility. Even someone who has never painted understands how pigment is applied or how a loom operates. We can imaginatively align our bodies with the bodies of those who made those artworks, feel the reach of the arm or the slow delicate tracing of a line by hand. Our minds cannot easily align with computer programs or printers. For anyone who has hit “send” on an email or double-clicked to open a program, the relationship between the finger’s click and millions, if not billions, of calculations, miles of circuitry burnt into boards and chips, the web of cables that encircles the earth, remains not simply mysterious but so beyond our everyday experience as to be largely incomprehensible. These artists plumb the depths of both: the intuitions we have of the analog, and the seemingly magical output of the computer.

The Santa Barbara Museum of Art is one of the finest museums on the West coast and is celebrated for the superb quality of its permanent collection. Its mission is to integrate art into the lives of people through internationally recognized exhibitions and special programs, as well as the thoughtful presentation of its permanent collection.

Santa Barbara Museum of Art, 1130 State Street, Santa Barbara, CA.

Open Tuesday – Sunday 11 am to 5 pm, Free Thursday Evenings 5 – 8 pm 805.963.4364 www.sbma.net