CSU Professor Dr. Frank P. Barajas will present “Cesar Chavez’s Life and Legacy in Oxnard” from 2 to 3 p.m. Saturday, March 29 at the Oxnard Public Library, 251 So. A., St. Oxnard. Learn about the life of famed worker’s rights advocate Cesar Chavez and his connections to the Oxnard Community

Editor’s note: Amigos805 welcomes guest columns, letters to the editor and other submissions from our readers. All opinions expressed in submitted material are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the viewpoint of Amigos805.

Frank P. Barajas. Courtesy photo.

By Frank P. Barajas / Guest contributor

If alive today, the famed organizer of farmworkers, César E. Chávez would be 98 years old March 31st. The commemoration of his birthday is a state holiday dedicated to the promotion of service and learning programs in California. To visibly honor his life and legacy that bettered the lives of los de abajo (the underdog), communities throughout the nation will take to the streets in celebration. Blood-red banners with a black, rigid eagle insignia centered within a hoary backdrop will wave in the hands of young and old marchers as they respond to bull-horned calls of: ¡Que Viva Cesar Chavez! ¡Que Viva Dolores Huerta! ¡Que Viva Los Campesinos (farmworkers)! Complemented by a repetitive crescendo of ¡Si Se Puedes (Yes we can)!

But who was this person and why is he important?

Analog to the Joad family in John Steinbeck’s Pulitzer Prize-winning novel, The Grapes of Wrath (1939), amid the Great Depression César’s parents lost their Yuma, Arizona homestead. After scouting for work in California, in 1938 César’s father relocated his family to Ventura County to toil in the sugar beet fields of the Oxnard Plain. In a 1975 autobiography authored by Jacques E. Levy, César described labor in el betabel (sugar beets) as feudal, “the worst kind of backbreaking job.”?Cesario, center, and siblings traveling like The Joads

Cesario, center, and siblings traveling like The Joads. Biography of César E. Chávez (CA Dept of Education). Courtesy photos

César also described the misery of migrant workers living in tents that just shielded them from the night’s bitter cold and leaked profusely when it rained as they tried to sleep. The conditions of sanitation were equally horrible: the water was often rancid and little to no personal privacy existed. My father confirmed such wretched conditions when he grimaced while viewing the opening scene of the movie La Bamba when Ritchie Valens reunites with hellion half-brother Bob at a Joaquin Valley labor camp.

My dad did not look forward to our family camping trips.

As an adult César commiserated, with righteous indignation, the oppressive character of agricultural work, largely defined by the fault lines of race (brown and white). This is a main reason why people followed him.

But before he was a labor union leader, he was a community organizer for the Community Service Organization in California. Headed by Fred Ross, César’s mentor, the same outfit that successfully mobilized a multi-cultural coalition to elect in 1949 Edward Roybal to the 9th District seat of the Los Angeles City Council.

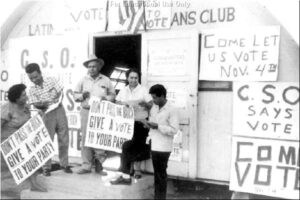

The CSO, supported by Saul Alinsky’s Back of the Yards Industrial Areas Foundation in South Chicago, empowered immigrant communities with a catena of programs: immigration, citizenship, voter registrations, and get-out-the-vote campaigns to name a few—including challenging police brutality and urban renewal projects that displaced the poor.

César’s reputation as a crackerjack organizer in San Jose attracted the attention of Ralph Helstein, leader of the United Packinghouse Workers of America. With Alinsky and Ross as brokers, Helstein commissioned César to create a CSO chapter in Ventura County’s City of Oxnard, his old stomping grounds, to serve as a basis to unionize men and women within citrus packinghouses.

Oxnard : Ventura County CSO headquarters, 1958. CC at the far right. Frank P. Barajas — National Park Service César Chávez Special Resource Study.

In the conduct of the CS0s house meetings strategy, César learned that the foremost moan of ethnic Mexican agricultural workers was agribusiness’s exploitation of government-sponsored Mexican immigrant workers known as Braceros to slash the prevailing wage rate and ultimately replace them. Why? To realize capitalism’s purpose: the maximization of profits.

After a resolute campaign of organizing and direct actions of protest, in 1959 the CSO temporarily forced Ventura County’s dictatorship of growers to abandon their use of exploited Braceros.

Three years later, in 1962, César separated from the CSO to create a union of his dreams in Delano, California, the National Farm Workers Association, later rebranded the United Farm Workers. Tapping into his network of CSO-trained activists throughout California, César enlisted fellow true believers. House meeting by house meeting, community by community while his wife Helen worked in the fields to financially support the family. One of his early recruits was Delores Huerta of the Stockton CSO.

People, current and former farm workers, joined César’s pursuit of La Causa as he articulated the plight of modern-day helots that involved: wage theft (often by ethnic Mexican labor contractors), wage slavery, sexual harassment, food insecurity (ironically), verbal abuse, substandard housing, and the absence of health insurance, vacation time, and old-age pensions.

Hence, César maintained that La Causa was the human right of farm worker families to live with dignity.

After a five-year struggle that involved strikes, picket lines, and boycotts nationally and internationally, in 1970 the UFW forced San Joaquin Valley grape growers, largely white, to sign union contracts. The fight in the fields and orchards by a rank-in-file of ethnic Mexican farmworkers in solidarity with their Filipino brethren inspired youth in rural and urban communities to join La Causa. One was Jessica Govea of Bakersfield whose parents were founding members of the Bakersfield CSO. She directed the UFW office in Delano and participated in grape boycotts in places as distant as Toronto, Canada.

In 1974, comparable to the expulsion of ethnic Mexican Chavez Ravine (now Dodger Stadium) fifteen years before, citrus worker families at Cabrillo Village in the City of Ventura faced eviction. This occurred again in 1978 at the Rancho Sespe labor camp between the cities of Santa Paula and Fillmore. In both instances, the ag bosses attempted to bulldoze their homes; the rationale was if the foundation of the community was destroyed the annihilation of the UFW would follow.

But in both instances, César’s UFW advised resistance which ultimately resulted in improved cooperative housing developments for the families of citrus workers in both communities owned by farmworkers.

Current residents of Ventura County, Barbara Macri-Ortiz of Italian descent raised in Ontario and Karen Flock of Norwegian ancestry who grew up in El Centro were two of a generation of students, from an array of backgrounds, who left and took time off from college to serve the UFW. As they learned by doing, both eventually entered careers to advance the housing needs of farm workers: Barbara as an attorney who completed the UFW’s Law Office Study Program and Karen as a project manager for the Cabrillo Economic Development Corporation.

Other activists of the 1960s and 1970s, inspired by the courage of César’s comrades, went on to serve their communities as educators, healthcare professionals, and social workers. Even if they were not farmworkers themselves, they, like me, came from families who recounted at the dinner table harrowing stories of migrant agricultural poverty, educational dysfunction, and racism.

César’s story is our story.

This is why César’s holiday is one of a day of service and learning. The work he performed is far from over and ours to continue.

— Frank P. Barajas is a lifetime resident of Oxnard and Professor of History, Faculty Early Retirement Program at California State University Channel Islands.

Editor’s note: Amigos805 welcome comments on stories appearing in Amigos805 and on issues impacting the community. Comments must relate directly to stories published in Amigos805, no spam please. We reserve the right to remove or edit comments. Full name, city required. Contact information (telephone, email) will not be published. Please send your comments directly to frank@amigos805.com